Light straw-clay (LSC) is an insulating wall infill material with a long global history. Along with other natural building methods like adobe, cob, and straw-bale, it is now increasingly popular among builders looking for healthier, more ecological building methods. For one, I am currently building and hosting workshops at a small light straw-clay project. Here’s a primer on LSC.

- What is light-straw clay?

- Advantages of light straw-clay

- How does light straw-clay work?

- Is light straw-clay really insulating enough?

- Is light straw clay a fire risk?

- Is light straw-clay legal?

- Is it expensive?

- TL;DR? Come to a workshop!

What is light-straw clay?

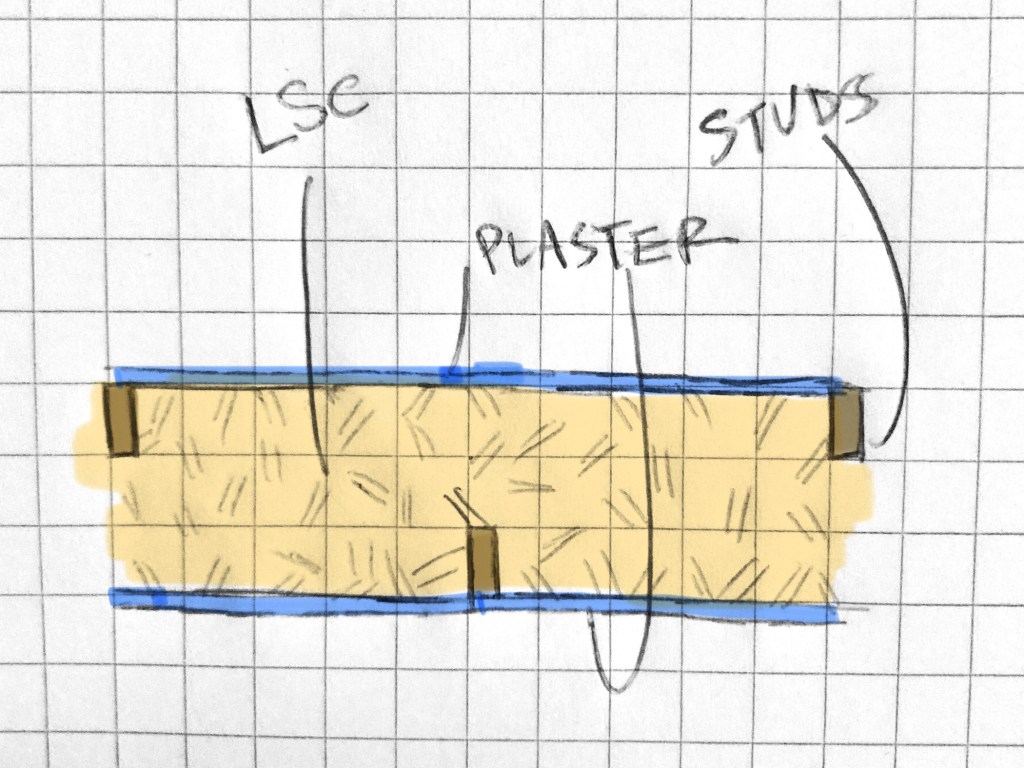

So what is light straw-clay exactly? It’s very simple: a mixture of straw and clay slip, tossed together like dressing a salad. The damp mixture is then packed into a wall cavity and dries into a surprising solid, sturdy wall. Afterwards, it is plastered for a beautiful and protective finish.

LSC was developed in the 20th century as an evolution from traditional earth-and-fiber wall infill methods, primarily wattle and daub, which has a long history of use in Europe.1 These methods were exported to New England to a degree, so there very well may be some old proto-LSC buildings hiding in your local historic neighborhoods.

“We are so accustomed to thinking of the old New England houses as structures covered with clapboards that we are in danger of forgetting what is underneath. . . . [I]f we rip it off many of the oldest buildings, we shall find behind it nothing more nor less than an old English half-timber house, built precisely as were the half-timber houses in the reigns of the Tudors or Stuarts. . . . [T]he spaces between the studs are ‘pugged’ with rough bricks or stones and coarse clay stiffened with chopped straw, also in the time-honored English manner,” wrote historian Harold D. Eberlein.2

The types of straw most commonly available here in the U.S. are wheat, rice, rye, barley and oat, because these crops are grown in large quantities. However, technically, any dry plant matter composed of thin, hollow stems would work. That is what makes it insulating: the hollow stems trap lots of tiny air pockets, which slows down heat transfer.

Advantages of light straw-clay

- Biodegradable: The ingredients, straw and clay, can safety return to the earth at the end of the building’s life, unlike synthetic materials that cause centuries and even millennia of pollution.

- Greenhouse-gas negative: If care is taken to avoid extra emissions from transportation and installation, light straw-clay can prevent emissions and store carbon that would otherwise be emitted to the atmosphere. This is because letting straw decompose, or burning it to dispose of it, as farms often do, would release CO2 to the atmosphere, while preserving it inside a wall traps the carbon in its solid state.

- Safe to touch: Straw and clay are perfectly safe (and even enjoyable!) to touch, unlike fiberglass insulation, which cause irritation (Note that they can still produce dust, and masks should be worn when working in dusty conditions, regardless of what kind of dust it is.)

- Great to plaster over: Light straw-clay walls provide a great, toothy surface for plaster to stick to, so you don’t need the extra step of attaching a substrate like wood lath or metal mesh before plastering. Natural plasters are often highly desired for their aesthetic, performance, and environmental advantages.

- Freedom of design: Light straw-clay is packed into a wall cavity, which means it can be used with any wall shapes (rounded corners, funky shapes) and thicknesses (customize to your insulation needs!). This is different from straw bales, which come in a predetermined size and shape, and are tedious to trim.

- Compatible with familiar building methods: Light straw-clay can be used to fill in the walls of a basically conventionally stick or timber framed structure, as long as the walls are thick enough to achieve the desired insulation value. This can be straightforwardly done with double stud framing.

- Can be retrofit into existing structures: It is possible to turn an existing building into a light straw-clay building, saving you the costs of building a whole new building.

Read on to learn about how LSC provides all these benefits!

How does light straw-clay work?

As you just read, the straw provides the insulation by trapping lots of tiny air pockets inside and around the stems. This is how insulation materials work: by immobilizing a gas.

A quick science lesson: Gases transfer heat much more slowly than solids because there are less molecules in them, per unit volume, so there are fewer molecules to get heated up, and they have to zoom around in microscopic space a lot more to bump into another molecule to transfer their energy to. Consider a vacuum-sealed thermos, which has even less stuff (almost nothing!) in between the two walls, which cuts off the conductive and convective routes for heat to transfer, leaving only radiative heat transfer. Vacuum-sealing is hard to do, though, so most insulating materials we use work by being mostly air, plus lots of thin “walls” that slow down the flow of air through them.

So what’s the clay for? It has two main jobs: sticking the straw together so it holds the shape once you remove the form, and keeping the straw dry. It’s also another line of defense against critter munching.

If straw gets wet and stays wet for long enough, it molds and decomposes into stinky mush—not helpful! Even if the walls are protected by a good roof, water has a tendency to get everywhere. Splashing rain, leaks, and water wicking up from the ground can threaten straw walls. Furthermore, the air is full of water vapor, which likes to condense on solids when the temperature drops, whether that be because the seasons change or because warm air has moved from inside the house to the colder outside.

How does clay prevent straw from getting wet? Rather than acting as a raincoat, it acts more like a big fluffy wool sweater. Clay can absorb a whole lot of water, which is why your face feels dry after letting a clay mask dry on it. So when water meets the clay-coated straw, it gets absorbed mostly by the clay. The clay holds on to the water, and when conditions dry up or warm up again, the water evaporates back into the air and floats away.

Some cool experiments (spray water on a block of LSC and a block of LS with no C) have shown that the clay coating really does help the straw bounce back to dryness impressively fast!

Modern LSC buildings have stood the test of time for decades already, and old light-earth buildings in Europe have also survived for many decades.

Is light straw-clay really insulating enough?

Yes, if you design the building to be well-insulating! The insulation value of LSC has been tested in multiple experiments by Design Coalition and Douglas Piltingsrud, which yield R-value ranges of 0.84 to 1.80 per inch, depending on how much clay/subsoil is in the mix and how dense it’s tamped.

So, for example, a 10″ thick LSC wall on the light side (R-1.8 per inch) in a double stud wall with offset 2×4 studs is about thick enough to meet the Massachusetts code, which specifies R(13+5) (R-13 in the cavities plus R-5 continuous).

You can simply go thicker or thinner, depending on your needs.

Is light straw clay a fire risk?

If properly built, the fire resistance seems to be acceptably low, and likely even better than standard construction. This is for several reasons:

- Higher density: The LSC is much more dense than the usual wall insulation materials like fluffy fiberglass. This means there is less air available to fuel a fire.

- Lack of gaps: When properly packed in place, there are no big gaps (draft tunnels) for air to flow.

- Sealed by plaster: The plaster on the surface of LSC is married to the material, as opposed to the air gap that tends to be present between wall sheathing and fluffy insulation. Plaster, being made of minerals, is far less flammable than wood sheathing and siding.

- Chars instead of melting: Synthetic materials, when set on fire, will melt back into a puddle, opening up space for air (fuel!) to flow. Organic materials tend to char into solids, remaining more of a barrier to air flow.

As you can see, the plaster is an important component. While not as many fire-resistance studies have been done on LSC, there are a few and they are promising. A Chiltern Fire Intl study cited by the DTI report showed that evne an unplastered LSC sample (29.6 lb/ft^3) survived a 1000 C furnace for 36 minutes. A Canadian study found that a 40 lb/ft^3 LSC wall, also without plaster, was penetrated only 2 inches after 4 hours of propane torching, making it “very likely meet the conditions required for a

fire resistance period of four hours.”

While builders such as myself might opt for a significantly less dense (as low as 10 lb/ft^3) mix to increase insulation for a given wall thickness, the fact that LSC walls should always be plastered adds a significant degree of fire-resistance.

Studies on plastered straw bales also provide support to the fire-resistance of plaster. A 2003 review by Bob Theis describes how plastered straw bales easily pass fire tests.

But perhaps most tellingly, light straw-clay has been added to the International Residential Code since 2015, which may be the biggest stamp of approval of all.

Is light straw-clay legal?

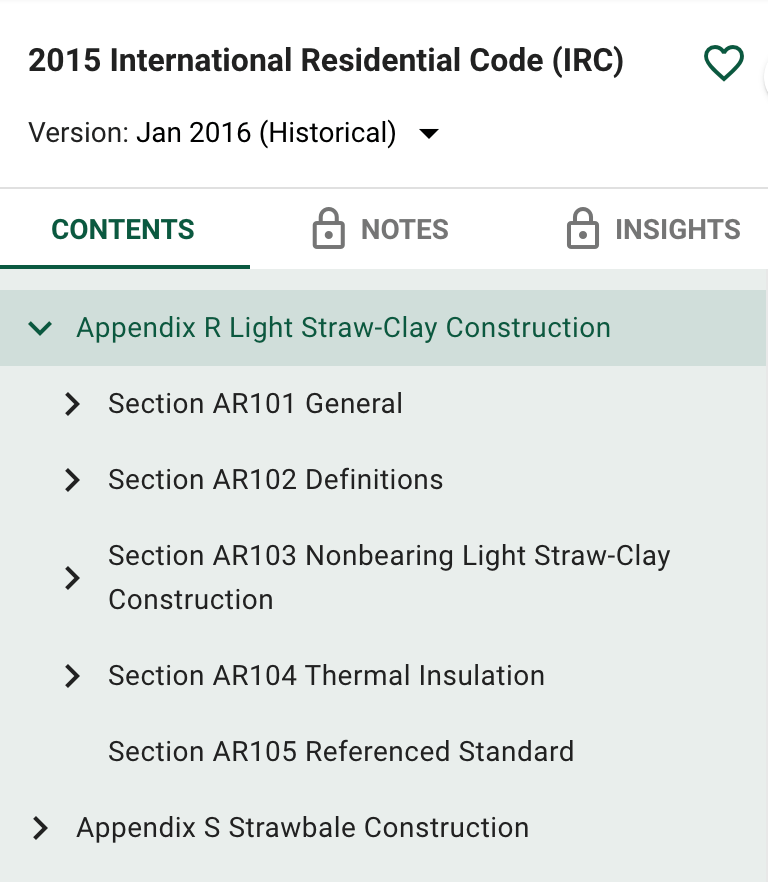

In a year worthy of much celebration, 2015, both light straw-clay and straw bale building were published in the International Residential Code (IRC) after being approved in 2013.3 Virtually all jurisdictions in the U.S. base their building codes off of the IRC, so this opened the door for adoption of these methods into local codes.

Not all jurisdictions have adopted the LSC appendix (Appendix R) yet, so you’ll want to check with your local department. It’s also worth mentioning that the lack of adoption doesn’t preclude all use. There are case-by-case approvals sometimes, and there are structures that don’t need permits (such as sufficiently small sheds, the bread-and-butter of us alternative builders).

Is it expensive?

I don’t have a lot of experience or information on how prices shake out for LSC houses, but from my general perception of natural building, I would consider it to be slightly more expensive, your time included, but with a very large range of possible cost.

While some things can drive the cost up (the labor of making and applying LSC, which is no small task, the fact that you’re doing something different at all), some things can drive the cost down (the opportunity to enlist community support via work parties, workshops, etc). Furthermore, if you factor in the environmental, health, durability, and even emotional benefits, it may become a very promising option.

There are plenty of examples of natural buildings built with a shoestring budget, as well as expensive and luxurious projects. At the end of the day, there’s an unlimited number of ways to build a house, and more and more people are looking at LSC as a great option for many climates.

TL;DR? Come to a workshop!

Reading not your thing? Want to learn more, and hands-on at that? Check out my upcoming workshops and events.

- An Introduction to Traditional and Modern German Clay Building, Frank Andresen https://www.networkearth.org/naturalbuilding/clay.html ↩︎

- The Architecture of Colonial America, Harold Donaldson Eberlein, 1915. As cited in The Natural Building Companion, Jacob Deva Racusin and Ace McArleton ↩︎

- Update on Strawbale and Light Straw-Clay Codes in the United States, Martin Hammer, April 25, 2017 https://www.thelaststraw.org/275258-2/ ↩︎

Leave a comment